How gaming transformed from a niche interest into the world’s biggest untapped marketing resource

What does the abolishment of third-party cookies mean for publishers?

June 1, 2021

Authenticity and influencer marketing in music media

June 22, 2021When the medium was in utero, not a single brand wanted to touch video games. Now, even the brands who don’t understand gaming in the slightest want a piece of it.

Video games have come a long way since Pong, to say the least. Before games had even entered the digital landscape, they were attracting controversy – remember when Dungeons & Dragons was supposedly a gateway drug to devil worship? Cue a few decades of Grand Theft Auto, Call of Duty, and other titles that consistently struck the wrong chord with an ageing population, and two things became clear. First, video games were making an insane amount of money, and second, nobody outside of that world wanted anything to do with them.

But throughout the 2010s, something changed. The explosive rise of live streaming, heralded mostly by Twitch but followed suit by Facebook, Youtube, and other platforms, was side-by-side with an explosion in video game popularity and sales. A tonal shift also occurred. Spurred by gaming’s increased visibility in non-gaming markets, it became more widely accepted to label oneself a gamer. Or label a company as catering to gamers.

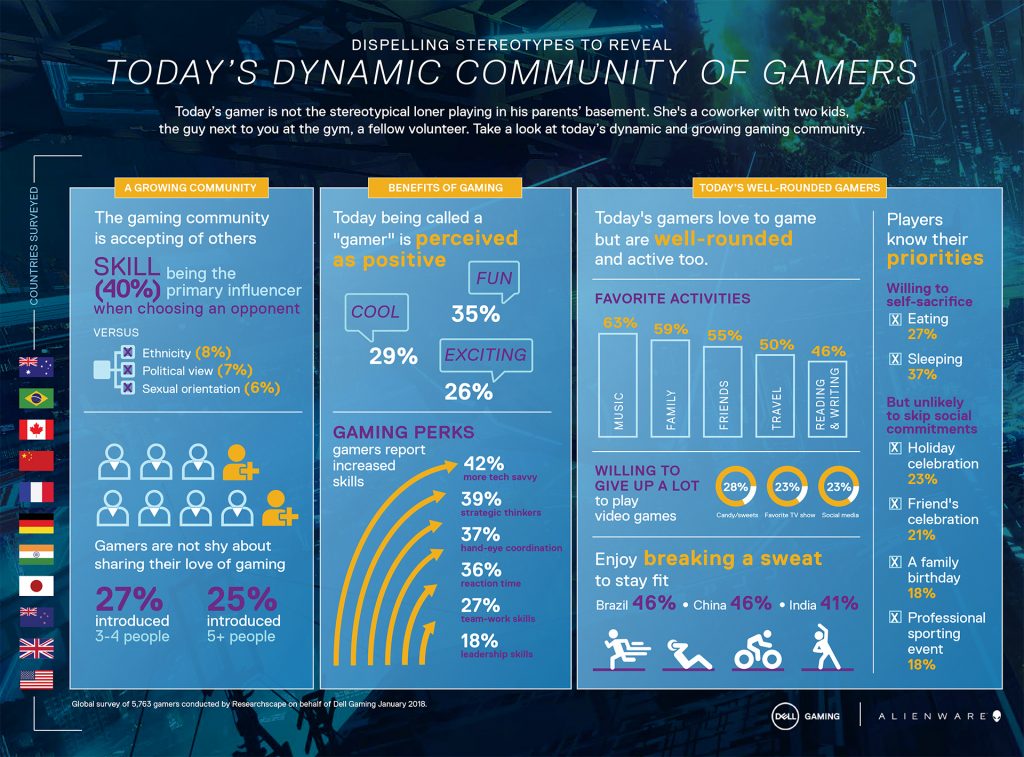

What does today’s gamer look like?

According to 2016 research by Dell, less than 1 in 10 respondents felt “judged”, “childish”, or “embarrassed” because of their video game hobby. A larger portion of female gamers was also identified by the research (as referenced in many similar studies), which works against long-held beliefs that the industry is geared towards men and men only. That said, it still has a long way to go.

Contemporary gamers aren’t defined by gaming as their sole interest, either. Dell reported that their respondents were also avid music fans (63%), lovers of travel (50%), and readers and writers (46%). This was reflected in an internal survey by Happy Mag, an Australian youth publication with a focus on music, the arts, and as of March 2020, video games.

After spending five years building an audience of music and arts lovers in Australia and around the world, Happy Mag reported that 67% of readers spend five hours or more gaming per week, 51% spend more than $50 on gaming per month, and 86% of their followers read at least one gaming-oriented article per day.

A more anecdotal shift is towards the belief that video games have become an art form akin to film, television, or novels. Spellbinding or narrative-driven games such as The Last of Us or Bloodborne represent some of the better told stories of our time, causing a planar shift in how games can be perceived.

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

In financial terms, the US gaming industry now outclasses the US film industry by as much as 1500%, according to figures gathered by The Numbers and Grand View Research (it’s worth noting these figures reflect pre-pandemic market size, nowadays video games would be outperforming films by an even higher factor).

All of this data points to one key finding: video games are becoming (or perhaps have already become) the world’s largest form of entertainment media. There are more players than ever and they have money to spend, so apart from video game developers and publishers themselves, who’s cashing in?

Some companies saw an easy alignment – energy drinks and sports brands (fashion, production, talent management, etc) were early adopters. Red Bull has played a major hand in the casual gaming and professional esports markets alike this decade, including the sponsorship of tournaments, esports teams, content production (a feature-length documentary on pro Dota 2 team OG included), and more.

Many talent agencies have signed esports athletes, professional Twitch streamers, or other prominent gaming personalities. Mercedes and Honda have previously sponsored the League of Legends championship series in the past, and of course, gaming-focused hardware brands such as NVIDIA, Alienware, Turtle Beach, and countless others are spending huge advertising dollars on these events, stars, and activations.

Further to the hardware front, you’d be hard-pressed to find an audio, computer hardware, or even furniture manufacturer who hasn’t released some kind of gaming-centric product in the last 5 years. Even IKEA is on the hype train.

A pie with many pieces (and how to get yours)

As gaming’s market share grows, so to will hungry brands who want a piece. Those who can’t produce a new product that appeals to gamers (for instance Audio-Technica creating their first gaming headset, a natural brand evolution) will aim to bludgeon their way into gamer’s hearts with more straight-out sponsorship deals.

Exclusive gaming events such as tournaments or conventions are obvious first points of sale here, but with more and more companies adopting a slow lean towards the world of gaming, partnership opportunities for savvier brand managers will increase.

The most successful events or campaigns in gaming capitalise on a few points; the medium’s near-rabid fanbase, the emotional weight even casual gamers put on their favourite titles, and the fact that as of 2021, many agencies, publishers, and content creators still aren’t doing it.

In this transitionary period where a great deal of brands are seeing gaming’s potential, content creators should seek to wear strong gaming audiences or strong ties within the gaming industry on their sleeves. Those who can marry the world of gaming with an existing area of interest such as music (as we’ve seen from Dell and Happy Mag’s research, the crossover is formidable) should be the first port of call for brands, as those crossover events are what continues to push video games (and therefore, the brands who champion them) further and further into the mainstream eye.

Below we’ve collated a number of recent examples of publishers, brands, and more who have achieved incredible results by knocking on gaming’s door. Enjoy the light entertainment: